CROSSING THE LINE

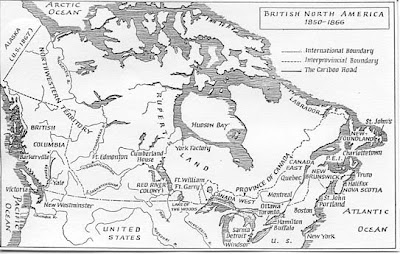

Today the Canada--U.S. border is celebrated as the longest undefended border in the world. But it wasn't always so. More than a century ago, as the Canadian provinces edged toward Confederation, some Americans cast their eyes northward. But Manifest Destiny wasn't their game. They were Irish Americans--Fenians--with a passionate fondness for their homeland and a passionate hatred for Ireland's British rulers. They had a daring plan. they would liberate Ireland. And they would do it --oddly enough--by invading Canada.

The Toronto newspapers were filled with talk of war. The year was 1866, and an alarmed Canada was arming itself against an invasion launched from the soil of its neighbour, the United States. Politicians pleaded for provincial unity against the aggressors assembled along the border. Britain hastily ferried troops across the Atlantic and deployed her warships along the Canadian coast. Had the United States, fresh from its victory over the rebel armies of the South, turned its war machine northward? Though the American doctrine of Manifest Destiny was a long-standing and legitimate Canadian fear, it was not American ambition causing Canadian concern. The attackers were not Union troops at all, but a group of Irish revolutionaries known as Fenians. And the "war" they had started-so emphatically captured in the headlines of the day was but the first of a series of ill-fated raids into Canada. The Fenians'objective was not to wrest a North American country free from British rule. Curiously, they were trying to free a European country from British rule.

The Fenian plan was to ransom Canadian territory gained in battle with London to secure Irish independence from Britain. At the very least, the Fenians hoped to draw Crown forces across the Atlantic to counter their threat to Canada, which would strip troops from Ireland to help ensure a successful revolt at home. They hoped, too, that U.S. ambiguity on the Fenian situation might lead to Anglo-American conflict, which would further serve their cause.

The Fenians were just one of many Irish revolutionary groups born of centuries of hardship suffered at the hands of Ireland's British rulers. All dreamed of an independent Eire free from subjugation to its neighbour across the Irish Sea. But from the United Irishmen revolt in 1798 to the Easter Rebellion of 1916, Irish uprisings met little success, each crushed by the weight of English military might. Unlike the others, however, Clann na Gael, more commonly known by its informal name "Fenians," began in America among the Irish diaspora. Their leader was Irish-born John O'Mahony, a member of a well-known nationalist family (his father and uncle both fought in the 1798 rebellion), who moved to New York in 1853 where he founded the Emmet Monument Society, a precursor of the American Fenianmovement. A corresponding movement sprang up in Ireland in 1858 under the name of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (IRB). This group was also referred to as Fenians, a name taken from the fanciful band of Celtic warriors called Fianna Eireann. Together, these two groups raised money on both sides of the Atlantic to support their goal of an independent Ireland.

Through marches, protests, conferences, and speeches, the Fenians took their campaign to American cities with growing Irish populations, like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, as well as to Toronto and Montreal. By the end of the Civil War, the movement's coffers were filling and membership swelling. For the Fenians, the end of this war had two profound benefits: cheap and ample supplies of arms, and battle-tried Irishmen fresh from serving both Union and Confederate armies. The Feniansperceived that the American public favoured them, but signals out of Washington were mixed. The administration of President Andrew Johnson took a public stand against any aggression towards Canada but acknowledged its ineffectiveness in suppressing Fenian designs. Certain factions in Congress were sympathetic to Fenian ambitions against Canada, however. The Irish voting block was growing in size, and politicians wanted to placate their Irish constituents. Too, many American were quick to remember Britain's support of the South in the Civil War, and that Canada, Britain's possession, had been the launching point of a raid into St. Albans, Vermont, by Confederate brigands. And, or course, Manifest Destiny remained a popular tenet.

At war's end, the Fenian movement in America split into two factions. One, led by O'Mahony, favoured the original aim of transferring funds and arms to the IRB in Ireland. But another, more radical faction, led by William Randall Roberts, a retired New York store owner, and composed largely of members of the elected Fenian senate, backed direct action-an assault on Canada. The radicals prevailed, and with a reluctant O'Mahony in tow, formulated their military strategy against British North America. Their slogan: "On to Canada!"

Canadian authorities began to take the Fenian threat seriously in December 1865, when they dispatched militia along the Niagara River following rumours of an impending attack. But the attack never materialized. Three months later, during a St. Patrick's Day rally in New York, Fenian speakers issued vitriolic declarations against Canada. Again, Canadian authorities called out the militia, this time ten thousand strong. And again the threat subsided. Despite the absence of any tangible offensive to this point, Canadians took the Irish revolutionaries at their word. This would soon change. Just when Canadians decided the Fenians were crying wolf, the attacks began.

In April 1866 Fenian leaders decided finally to put their plans into action. The O'Mahony wing, anxious to regain the mantle of Fenian leadership, suddenly adopted a militaristic tack. They drew their forces together at Eastport, Maine, with the intention of invading Campobello Island, a few miles over the border in New Brunswick. Portland, Maine, 175 miles southwest of Eastport, teemed with Feniansstopping on their way to the rallying point. Eastport itself was crammed with Irishmen and enterprising New England sea captains vying for the lucrative business of transporting them across Passamaquoddy Bay. Five Fenians managed to make it across the border to Indian Island, threaten an official, and capture a Union Jack, but this was the extent of the Fenian offensive. A combined force of Canadian militia and British regulars, numbering around five thousand, lined up against the Fenians. The HMS Duncan, a 3,727-ton behemoth laden with troops and eighty-one guns, was dispatched to Passamaquoddy Bay and soon joined by four other British warships. From the south, an American detachment of three hundred soldiers arrived at Eastport, ostensibly to enforce President Johnson's declaration of neutrality. The would-be invaders withdrew in the face of superior numbers, but not before American authorities seized fifteen hundred rifles and one hundred thousand cartridges. TheFenians' first attempt against Canada fizzled without a shot being fired. John O'Mahony, a reluctant supporter of his faction's efforts, fell out of favour as a leader.

Of all the men charged with leading these military forays, however, John O'Neill became the most renowned. Described by contemporaries as egotistical and credulous as well as fearless and honourable, the six-foot-tall Irishman, according to W.S. Neidhardt's Fenianism in North America, "combined an undoubted military bearing with a rich sonorous voice, which lent to his presence a certain charm." Emigrating from Drumgallon, County Monaghan at age fourteen, O'Neill enlisted in the American army after dabbling unsuccessfully in the publishing business. He first saw action in 1857 as a dragoon in the so-called "Utah War" against Mormon militias and then as a cavalry officer in the Civil War, distinguishing himself under fire and acquiring a reputation as a daring fighting officer. At the end of his career in the U.S. army, O'Neill found his way to William Randall Roberts-and his militaristicFenians, receiving an appointment as colonel in their army. In his Nashville, Tennessee district, O'Neill organized a detachment of six hundred men and marched them north. It was under O'Neill's command that the Fenians had their only, albeit fleeting, success.

On May 31, 1866, O'Neill led a force of eight hundred men from Black Rock Ferry near Buffalo, New York, across the Niagara River into Canada (he had inherited command of the Fenian army from General William F. Lynch, who mysteriously went missing at the appointed hour of attack). A telegraph report described "Fenians mounted two deep upon horses; Fenians in lumbering wagons, carrying boxes of ammunition; Fenians on foot, whistling bayonets about their heads, frantically leaping mud-puddles, and shouting `Come on.'" The Canadians had misjudged the Fenians-the non-event at Campobello and a series of false alarms had made them complacent. They disregarded warnings of aFenian move across the Niagara up until the last moment. Reports of the Fenians' demise had been premature.

With their militia disbanded, the six hundred people of Fort Erie, Ontario, across the Niagara River from Buffalo, were virtually defenceless, and their village fell quickly to the Fenian army. To thwart the arrival of Canadian reinforcements, O'Neill had all telegraph lines severed and ordered sections of the Buffalo and Lake Huron Railroad lines destroyed. From Fort Erie, under green battle flags embroidered with gold harps, in green shirts and black belts, the Fenians proceeded toward Ridgeway, ten kilometres west.

The report of the invasion came as a shock. Canada was in an uproar, and authorities called out the full militia the next day. Fortunately for O'Neill and his men, the first group they encountered was an ill-trained militia detachment of 840 Canadians under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker. The militiamen had to fight the Fenians alone-British forces under Colonel George Peacocke had been expected to join their ranks but were delayed. O'Neill was aware of the planned combination of Canadian militia and Imperial troops, and took advantage. The Irishmen, mostly hardened Civil War veterans, soon held the upper hand.

But not for long. The tide of battle began to swing from the Irishmen to the Canadians. Then theFenians orchestrated a crucial feint. With insufficient horses for an effective cavalry unit (Fort Erie farmers hustled their animals away at the first sign of the invaders), the Fenians nonetheless used what few horses they had to charge the militia. The Canadians panicked, unaware that the handful of men on horseback was not the vanguard of a large cavalry unit but the entire unit. The Canadian line broke as the foot soldiers fled at the hands of this ghost cavalry. Booker gave the order to form Wellington squares, a classic defence against mounted troops, requiring foot soldiers to cluster in tight formations. With their targets neatly bunched, however, the Fenians lay down a deadly hail of bullets as their handful of horsemen gave way. Booker surrendered the field at the Battle of Ridgeway with nine men dead and thirty-eight wounded.

O'Neill, perhaps sensing his encounter with such a poorly prepared detachment had been mostly good fortune, withdrew from Ridgeway to the relative safety of Fort Erie. As the troops made their way back, however, a rear guard of 150 men at Fort Erie was engaged in battle with a Canadian force of about seventy. Under the command of Brigade Major John Stoughton Dennis, the Canadians had sailed up the Niagara River on a commandeered tug to attempt, at Booker's command, a rear assault on theFenian position. But the superior number of Fenians reinforced by their returning comrades easily repelled them. Six Canadians lost their lives in the attack; fifty-four were captured. Dennis, after ordering a retreat, abandoned his men and evaded capture himself by hastily shaving his moustache and disguising himself as a local labourer. One officer at the scene labelled him a "Poltrooney scoundrel." As a result of his less-than-heroic actions Dennis faced charges but was later exonerated.

~~~~~~~~

By June 3, twenty thousand militiamen had mustered, ready for against the invaders. Peacocke's force finally arrived at Fort Erie and entered unopposed. Learning of the advancing army and aware that he could expect no reinforcements, O'Neill had abandoned the village and retreated to the Niagara River, where he and most of his compatriots were picked up by the American warship toss Harrison and arrested. O'Neill was charged with breaking United States neutrality laws, but the charges were later dropped.

Less than a week after O'Neill's fleeting victory, and despite the short-lived gains at Fort Erie, anotherFenian band crossed the Canadian border, this time from Vermont, occupying Pigeon Hill in Missisquoi County, Quebec. The attack was designed by General Thomas Sweeny, commander-in-chief of theFenian army and architect of the Fenian military campaign, as a complementary pincer move with O'Neill's Ridgeway action. He would attack the rear of British and Canadian forces from the east as O'Neill's men attacked from the west. Though O'Neill's troops were no longer a threat in the west, the attack from the east proceeded. But Sweeny, who had lost his right arm while serving as a brigadier-general in the U.S. army, was arrested in Vermont by American authorities before he could lead the attack into Canada. Brigadier-General Samuel Spear stepped into his place.

Over one thousand strong, the Fenians marauded and looted their way through the sparsely populated Quebec towns of St. Armand and Frelighsburg, which did little for the cause of Irish independence. Under presidential orders, American troops seized the expedition's supplies in St. Albans, Vermont. Meanwhile, at the Battle of Pigeon Hill, a cavalry charge by the Royal Guides sent the Fenians fleeing towards the American border, where Spear and his officers surrendered to U.S. authorities. TheFenians' second and last "victory" met an abrupt end.

With these failures, the Fenian movement appeared to disintegrate. Scores of Fenian soldiers languished in Canadian prisons, and the organization roiled in financial plight. A March 1867 Fenianuprising in Ireland was quickly squelched, due partially to the failure of the remaining members of the O'Mahoney faction to get guns to Ireland in time. Instead of fighting the British, the Fenians engaged in internal spats. But nearly two years later, on April 7, 1868, Fenians had a further, more nefarious impact on Canadian life. Thomas D'Arcy McGee, MP, and Father of Confederation, was shot in the neck while returning home from a session of parliament --Canada's first political assassination. Irish-born and a principal force behind the "Young Ireland" nationalist movement of the 1840s, McGee had recently advocated peaceful means for freeing Ireland. His vocal criticism of the Fenians' violent tactics apparently cost him his life. Though not officially labelled as a Fenian, a young Irishman, Patrick James Whelan, was sentenced and hanged for the murder. Few doubted his motives.

Convinced that massive military action was no longer feasible and shouldering the blame for the Brotherhood's ongoing money troubles, William Roberts resigned his leadership of the Fenians in 1867. John O'Neill, the "Hero of Ridgeway," became president on January 1, 1868. O'Neill, however, had not abandoned his militaristic inclinations. On May 25, 1870, he led an attack on Eccles Hill, Quebec, close to the site of Samuel Spear's failed raid four years earlier. O'Neill strove to gain a foothold on Canadian soil in hope that the resulting excitement would once again rally vast numbers to the Feniancause. Amply warned, Canadian militia under the command of William Osborn Smith met them at Eccles Hill. As assistant adjutant general of a battalion stationed across the frontier south of Montreal, Smith had experience discouraging Fenian incursions. Support for O'Neill, on the other hand, had eroded following quarrels between him and his senate. He led a disappointing two hundred men into battle. But he was also foiled by another factor-his staff had been infiltrated by a spy, Henri Le Caron.

O'Neill believed Le Caron, a former officer in the U.S. army and sworn member of the FenianBrotherhood, to be a Frenchman opposed to British rule of Canada. He was in fact Thomas Miller Beach, an English agent. O'Neill so trusted Le Caron that he appointed him to the post of major and Military Organizer in the Service of the Irish Republic. The spy even accompanied O'Neill on a secret meeting with President Johnson, the details of which, along with every other Fenian move, were dutifully reported to Ottawa and London. Thus the British and Canadian militaries stayed one step ahead of Fenian plans.

At first O'Neill delayed his attack on Canada as he awaited a detachment of four hundred men from New York (which never arrived). This gave the Canadian militia time to secure Eccles Hill. Almost immediately after crossing the border, Fenian forces came under steady fire, and like a replay of four years before, many broke rank and ran to American soil. Smith's militia suffered no casualties. O'Neill, disgusted at his men's performance, heatedly admonished them from his observation post in a farmhouse on the U.S. side. In the midst of his tirade, he was again arrested and charged with violating U.S. neutrality laws. This time he was convicted and sentenced to two years imprisonment. But he was granted a presidential pardon and only served three months.

Though the IRB was still active for several more years in Ireland, by the early 1870s the Fenians in North America began steadily losing adherents. Nevertheless, despite O'Neill's public statement that he was abandoning any further campaigns, he led one final attempt on Canada in 1871. He had been persuaded by William O'Donoghue, a U.S. citizen who had been a member of Louis Riel's provisional government in Manitoba in 1870 before assuming the position of new leader of the dwindling Fenianmovement. Together O'Neill and O'Donoghue led a group of thirty-five men into Manitoba and seized an undefended Hudson's Bay Company post at North Pembina. Though Le Caron had related O'Neill's plans to Canadian authorities, it was the Americans who thwarted the Fenians. Pembina lay in disputed territory between the United States and Canada, so American troops followed and placed the invaders under arrest. When U.S. courts decided Pembina was in Manitoba, the Fenians were released.

Thus ended the Fenian dream of freeing Ireland by capturing Canada. The organizers never realized the support they had anticipated in the U.S., and Fenianism failed to attract any following in Canada. The enmity between the Irish and the English, so sharp in the British Isles, was muted in the New World. Many Irish Americans were willing to make financial contributions to free Ireland but few, it turned out, were willing to take up arms.

While they failed to free one country, the Fenians did help create another. External threats from the south boosted Canadian nationalism in the pre-Confederation period and helped unite the British North American colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec into the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. The Fenians spawned some successor movements in the late nineteenth century, among them the Irish National Invincibles in Ireland and the Triangle in the U.S. Each was dedicated to Irish independence and each blamed for several murders, but the most notable product of the Fenianlegacy was a group founded by former IRB member, Arthur Griffith. In 1905 he named his new Irish independence organization Sinn Fein, Gaelic for "Ourselves Alone." For years reviled as the political arm of the Irish Republican Army, Sinn Fein has recently achieved a new level of respectability by forging what is hoped to be a lasting ceasefire on the part of Irish republicans. While some hurdles still exist, notably the decommissioning of republican arms, Sinn Fein has taken its place within the Assembly, a democratically elected body formed to find peaceful ways to finally bring peace to Northern Ireland.

The Fenians won the Battle of Ridgeway, June 2, 1866, more by luck than by skill. Thinking the fewFenians on horseback were the vanguard of a large cavalry unit, the Canadian militiamen panicked and turned to flee when their leader ordered them into square formations. It was a mistake that facilitated the Fenian charge. Nine Canadians were killed, thirty-eight wounded. Fenian losses, though fewer, are unrecorded.

Though Fenian leader John O'Mahony originally thought invading Canada unstrategic, he was persuaded in April 1866 by more militant Fenians to attack Campobello Island, just over the U.S. border in New Brunswick. The attack failed, and O'Mahony lost the leadership of the Fenianmovement.

General John O'Neill twice led Fenian troops into Canada. In 1866, he had a fleeting success at Ridgeway in the Niagara Peninsula, but his 1870 invasion of Quebec was a rout. He was convicted of violating American neutrality laws, fined ten dollars, and sentenced to two years imprisonment. A presidential pardon released him in three months.

A spy also contributed to Fenian undoing. Thomas Miller Beach, an English agent, presented himself to John O'Neill as Henri Le Caron, a Frenchman opposed to British rule of Canada. Le Caron was so convincing he infiltrated the highest levels of the Fenian Brotherhood, then dutifully made reports to his masters in Ottawa and London.

~~~~~~~~

By Michael Westaway McCue

Response:

1) Imagine you were an Irish born immigrant living in Canada in the 1860s. Would you support the Fenians raiding Canada or feel more obligated to support your new Canadian brothers and sisters in defending your new land. Write a five paragraph response which explains your thinking. Be sure to make specific references to the article Crossing the Line by Michael Westaway McCue.